- Home

- Abi Elphinstone

The Dreamsnatcher Page 4

The Dreamsnatcher Read online

Page 4

Moll’s stomach twisted into a knot. ‘This Dream Snatch . . . I’ve seen it before. It’s like I said last night to Oak. It isn’t a nightmare, is it? It’s a memory.’

Mooshie fiddled with the hem of her pinafore, avoiding Moll’s eyes.

Moll stiffened. Something painful was happening inside her mind: a terrible memory, locked so deep inside her she thought she’d never find it, was sloping towards her.

It was a dark night, the forest muffled by snow, and she was hiding in the undergrowth by the river, not far from the drum and the rattle and the figures. Skull’s mask was there, floating before her.

She gasped.

‘I – I’m by the river and – and I’m not alone with the cloaked figures. There’s more to my nightmare than what I’ve seen before! There are other people with me only I can’t see their faces.’

Mooshie shifted on the grass but said nothing.

Moll felt the memory fading. ‘What happened? What am I remembering?’

Mooshie shook her head. ‘You’ve no idea who you are, Moll.’

‘Who am I then?’ Moll whispered. ‘And what does Gryff have to do with it all?’ Her voice crumbled into a shiver.

But this time Mooshie shook her head. ‘Oak needs to tell you, Moll – he’s the head of the camp.’

She tried to gather Moll into her arms, the way she did almost every time the nightmare came for her. But Moll scrambled away.

She stared straight ahead, a knot of fear fixing inside her. Things had been difficult before. But now they were a whole lot worse: she was more of an outsider than ever. And worse than that, somewhere not so far away, Skull was hatching a plan to kill her.

‘Wait by the fire, Moll, and I’ll fetch Oak.’ Mooshie’s eyes had filled with tears again, but she brushed them away and stood up. ‘It’s time you two talked.’

Moll made her way towards the fire in the middle of the clearing where Patti was scraping the last of the porridge into a bowl. She and her husband had been members of Oak’s camp for as long as anyone could remember and, while their daughter, Ivy, was easily the most alluring young woman in the clearing, the same could not be said about their son, Siddy, who combined a hopelessly misdirected enthusiasm with very little common sense. And there was a baby too, but she spent most of her time eating soil and sticking twigs in her ears. Excepting Ivy, Patti had it hard.

Today she was flaunting a purple waistcoat over a lilac blouse and a ruffled lavender skirt. Since the day she turned thirty, Patti had refused to wear anything other than purple. Most of the time she looked like a giant bluebell, but she was the best hawker the camp had; rumour had it that she had so much charm she could sell a toad for a small fortune.

Moll perched on an upturned log, her thoughts whirling.

Patti pulled the kettle back from the fire and passed Moll a steaming cup of raspberry leaf tea. ‘Here, drink this.’ She smiled. ‘And there’s one bowl of porridge left.’

Moll poked a spoon into the porridge, but her mind was miles away. Why was Skull after her and Gryff? She scoured the trees beyond the clearing for the wildcat and thought she glimpsed a movement of grey-black stripes. For a second, things felt just a tiny bit better.

Moll ate a mouthful of porridge and looked across the fire. Folded into a threadbare armchair he’d taken three days to haul from his wagon, and a further three weeks to stitch with the saying ‘Sometimes I sits and thinks; sometimes I just sits’, was Hard-Times Bob, Oak’s uncle and Cinderella Bull’s brother. And he was doing what he did best in the mornings: taking a nap.

Moll finished her porridge, then looked back up at Patti. ‘You Elders know about Skull’s Dream Snatch, don’t you? That’s what you speak about late at night round the fire. I’ve heard you.’

Patti looked about to deny it, but when she saw Moll’s glare she nodded.

‘You all knew and I didn’t!’ Moll said.

‘Only the Elders knew.’ Patti reached for a broom and began sweeping up scraps of food. ‘And that was because we needed to keep you safe. If we hadn’t told you about the boundary, you’d have crossed into Skull’s camp years ago. You and Siddy are always off exploring places.’

Moll knew Patti was probably right but she said nothing. There was only one person she felt like talking to now and, as she glanced up at the rope swing on the other side of the clearing, Patti seemed to read her thoughts. Hands on hips, Patti stood up. ‘Oi! Siddy!’ she shouted. ‘Over here – now! And take that ridiculous scrap of paper out of your mouth! Your father might smoke his tobacco after breakfast, but you’re only twelve and you look ridiculous!’

Siddy charged into the feeding chickens, sending them flying into a nearby wagon. He only wanted one thing in life: to be like his father. Jesse could tickle trout out of the river with his hands and he smoked hand-rolled cigarettes. So Siddy had to make do with catching minnows in jam jars and stuffing bits of paper into his mouth. He’d even admitted to Moll that it tasted disgusting, but had said, ‘A man’s got to do what a man’s got to do.’ Moll had no idea what a man had got to do, but she was pretty sure Siddy wasn’t doing it.

Siddy made one more swing for Rocky Jo, then sidled back towards the fire. As he approached Moll, he dipped his flat cap, just like his father always did.

Patti sighed. ‘Your shirt needs a wash, your hair’s all over the place and your shorts are covered in mud. Have I taught you nothing?’

Siddy beamed, which made his ears stick out even further. ‘You’ve taught me lots, Ma, but I haven’t learnt anything.’

Patti clouted him round the head, but he only grinned harder. Then he looked Moll up and down, his paper cigarette still lodged between his lips. ‘You OK?’

Moll didn’t look up. She didn’t need to – not with Sid. Ever since they were small, Moll and Siddy had gone around together. From an early age, it had been clear to everyone in the camp that Moll was going to be a terrible hawker. Her wire flowers were always slapdash (they looked more like wilting weeds than freshly-picked chrysanthemums) and during her first outing selling her goods in the village she had been so foul-tempered to customers who didn’t want her flowers that Mooshie and Patti had vowed never to take her again. But, with Siddy, Moll could be herself. They shared a mutual love of finding stuff and doing stuff; searching for woodpecker nests and building dens had bound them far closer than wire flowers could have ever done.

Siddy looked from Moll to his ma. ‘What’ve you gone and said to her? You been giving her grief over spying on Skull? I heard she was only trying to get Jinx back!’

‘I think you’d better take a seat, Sid,’ Patti said.

Siddy plonked himself down on to the log next to Moll while Patti busied herself with the dirty pans on the other side of the fire.

‘It’s Skull,’ Moll mumbled from behind her hair. ‘He – he’s after me and Gryff.’

Siddy frowned. ‘You and Gryff?’

Moll nodded. ‘And now everything’s dreadful.’

Siddy shook his head. ‘I don’t understand. Tell me what you saw in the Deepwood, Moll.’ He paused. ‘Tell me everything.’

And Moll did. But she left out one thing. Gryff had touched her and that was a secret she wasn’t ready to share.

Siddy blew out through his lips. ‘So Skull’s got a Dream Snatch and he’s using it to summon you and Gryff?’

Moll sunk her head into her hands. ‘Yes. And I don’t even know why because Oak’s out chopping logs so all I can do is sit here and eat porridge until he comes back.’ She kicked the ground. ‘And now Florence and the others will find out and call me an outsider all over again.’

Siddy lowered his voice. ‘None of this changes anything, Moll. Oak’s camp will always stand by you, no matter what you go around saying. You should know that by now.’

For a moment, the knot inside Moll loosened and then she thought of Skull squeezing the wax figure through his hands. ‘But I’m different from the others. Proper different – not just my eyes and my beginning now

.’

Siddy shrugged, pulling his pet earthworm, Porridge the Second, from his pocket. ‘Different’s good – you just can’t see it yet.’ He prodded his earthworm. ‘Isn’t that right?’ Porridge the Second only ever wore one expression, a sort of long-suffering look of indifference, but it satisfied Siddy and he took an imaginary puff of his paper cigarette.

Moll shook her head. ‘I shouldn’t have let that boy in Skull’s camp see me. Now Skull knows where I am.’ Her shoulders drooped. ‘Why do I always go and mess things up?’

Patti swept a pile of scraps round the fire towards them. ‘It’s what makes us real, Moll,’ she said. ‘There’s a crack in everyone and everything, but that’s how the light gets in.’

‘Wish I didn’t have so many cracks,’ Moll muttered. ‘I’m like a smashed-up eggshell, me.’

‘What’s this, Moll?’ came a voice as rough as sandpaper from the other side of the fire. ‘You planning another catapult attack on the chicken eggs with Siddy?’

‘Not this time,’ Moll said glumly.

Hard-Times Bob shot a glance at Patti, who just nodded, then he let out a low whistle. ‘So you know about the Dream Snatch, eh?’ He adjusted the snakeskin binding on his hand, Mooshie’s latest (somewhat questionable) cure for his arthritis.

Moll and Siddy nodded.

Hard-Times Bob was an old man who had the posture of a tortoise, with skin as shrivelled, and stumps of black, decaying teeth, despite the hedgehog paw he carried which was meant to stave off toothache. But he could dislocate every bone in his body and fit through the rungs of a ladder – and that counted for more than shrivelled skin and stumpy teeth.

Hard-Times Bob yawned. ‘Not like me to be napping through things like this.’

Patti raised her eyebrows. ‘It’s exactly like you, Bob.’

Hard-Times Bob looked at Moll. ‘So Oak’s told you all about the Bone—’

‘That’s enough, Bob!’ Patti threw him a warning look. ‘Oak’s not back in the clearing yet; he’s still to talk with Moll.’

Moll leapt up and rushed over to Hard-Times Bob. ‘Tell me, Bob,’ she urged, kneeling by his armchair. ‘Why is Skull after me and Gryff?’

For a moment, Hard-Times Bob’s face looked torn, then it shut like a cupboard door. He looked over at Florence and another girl peeling potatoes on the steps of a wagon. ‘Why don’t you and Siddy help the girls out with the feast preparations until Oak gets back?’ Florence looked up from the potatoes and smiled, her auburn ringlets falling in perfect curls round her face. ‘I bet they’d appreciate your help.’

Moll stood up, ready to storm from the fire. Then Hard-Times Bob winked. ‘Would it help if I dislocated anything – just until you speak to Oak?’

Moll was in two minds but, when Siddy came bounding round the fire to see, she knew she didn’t want to miss out. ‘Maybe your elbow,’ she mumbled.

Hard-Times Bob’s arms disappeared into his waistcoat, his silver watch chain jiggled and, after several seconds of wriggling and wheezing, he held up a very floppy arm. And then his hiccups started; he’d had them for nearly thirty years now, but they were always worse after a dislocation.

Despite everything, Moll smiled.

Patti bustled round and patted him on the back. ‘You’re not remembering to cross your boots before bed, are you? Prevents cramps and hiccups. You should know that by now.’

Hard-Times Bob rolled his eyes. ‘You think you’ve got it hard, Moll . . .’

But Moll was no longer listening. Oak was back in the clearing, laying down a pile of logs before the bender tent. His shirt was browned from the bark and his neckerchief flecked with wood chippings. Moll watched as Mooshie arranged the logs into a stack and Oak made his way towards the fire.

The camp clattered on – chickens screeched, a greyhound barked and children laughed – but those gathered round the fire were silent.

Oak stood before them, his hands in his pockets. ‘Come on, Moll. Let’s walk to the glade.’

Moll held his gaze. Oak had taught her the ways of the forest when she was little and he’d showed her how to carve catapults and animals from the trees, but, as she looked at him now, she felt that old, familiar world sliding away. She’d trusted Oak – and Mooshie – but they’d been keeping secrets from her, and she had a horrible feeling that the Dream Snatch was just the beginning.

Over the years the gypsies had worn a path through the trees towards the glade and, as Moll walked down it beside Oak, the leaves on the beech trees shimmered in the sunshine, brushed into flutters by the morning breeze. Moll thought of the Deepwood – so full of shadows and darkness compared to all this. She glanced around, past the sprigs of cow parsley shooting up among the ferns that lined the path, hoping that Gryff might be somewhere nearby. But he’d be resting in the hollow of a tree now, or curled up in the tangled undergrowth after his morning hunt, and she knew that no amount of whistling or calling would bring him close.

Oak ducked beneath a low-hanging branch and looked back at Moll. ‘I’ll need to start at the beginning for you to really understand,’ he said, ‘because you’re part of something, Moll. Something that goes back a long, long time.’

Moll’s heart quickened.

Oak waited until they were walking side by side again. ‘Over three hundred years ago my ancestors, the Frogmores, came to Tanglefern Forest. They settled in the Ancientwood, inside the Ring of Sacred Oaks, because they believed in the old magic said to be rooted here – the magic that stirred before the beginning of time, in the silence of the first dawn.’ He looked around. ‘It’s been with us ever since, this magic. It’s in the spirits of the wind and the trees, in the gurgling of the rivers and the grains of soil. You only have to lay your head against the earth to hear the old magic moving and turning. It’s the goodness and the stillness at the heart of everything.’

Moll stooped to pick up a stick and tapped it impatiently against the trunks of the trees she passed. This part she knew; Oak’s stories about his ancestors were campfire favourites.

Oak went on. ‘Only most people move so fast they don’t see the old magic any more. They’re too busy worrying about other things that they forget what’s really important. But, where ordinary folk see a feather fall, our people see the wind spirit fluttering between each fibre.’

‘I know about the old magic,’ Moll groaned. ‘I’ve learnt about the tree spirits and the water spirits and the wind spirits AND the earth spirits! You talk about them all the time.’

Oak shook his head. ‘Moll, there’s a difference between knowing and understanding. You’ve only scratched the surface of the old magic. But it’s stirring again now – deeper and more mysterious than anything you’ve ever known – and this time it’s calling for our help.’

They walked further into the trees, past the very first beech Oak had taught Moll to climb, and on past the silver birches the camp’s cobs were tethered to. Moll smiled as she glimpsed Jinx, who looked up and whinnied as they walked on by.

Oak steered Moll’s attention back to his words. ‘Our roles – mine as head of the camp, Cinderella Bull’s as Dukkerer, our fortune-teller, and Mooshie as the Keeper of Songs – they all fall to the Frogmore family, even though we’ve welcomed two other families into our camp, right?’

Moll scrunched up her nose. ‘This is slippery talk, Oak; how’s this anything to do with me?’

Oak ignored her. ‘And those in camp over thirty years of age form the Council of Elders, whatever their family name.’

‘Mmmmmn.’

‘Well, there’s another role in our camp – probably the most important one – and the only one I’ve never gone speaking about before. Not to you anyway.’

‘What is it?’

Oak paused. ‘The Guardian of the Oracle Bones.’

Moll stared at Oak blankly. Oracle Bones? She hadn’t heard talk of those before.

The path widened into the glade. The spring bluebells had been and gone but the grass there was now long and lush. Mol

l noticed Oak’s son, Domino, resting high up in the branch of a yew tree on the outskirts of the glade. So Oak had the Ancientwood guarded during the day now as well; Moll tensed as she remembered why.

Oak and Moll sat down beneath the oldest yew in the glade and, as Oak spoke, he turned the leather pouch containing his talisman over in his hands. ‘The story goes that there used to be a silver stag that lived in Tanglefern Forest, with sixteen points on its mighty antlers. It was said it was the oldest and wisest beast in the land. On the day it died our ancestors found it and took its bones – and these sacred relics became the Oracle Bones. Our ancestors believed that the Guardian of the Oracle Bones, a gypsy chosen by the Council of Elders, could carve one question into the bones in his or her lifetime and it would be answered by the old magic. The very first Guardian was worried, even then, that folk were losing sight of the old magic so he carved the bones, asking them if the old ways were in danger. He tossed them into the fire and, on removing them, he interpreted the cracks.’

A ripple of excitement fluttered through Moll.

Oak’s eyes were shining now, dark and deep. ‘They revealed a message, a foretelling, called the Bone Murmur.’

‘What did the Bone Murmur say?’ Moll asked quietly.

Oak drew himself up and, when he answered, every word tingled down Moll’s spine. ‘The bones said this:

There is a magic, old and true,

That shadowed minds seek to undo.

And storms will rise; trees will die,

If they free their dark magic into the sky.

But a beast will come from lands full wild,

To fight this darkness with a gypsy child.

And they must find the Amulets of Truth

To stop dark souls doing deeds uncouth.’

Everdark

Everdark Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll

Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll Rumblestar

Rumblestar Jungledrop

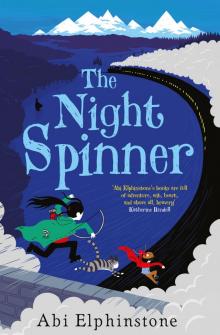

Jungledrop The Night Spinner

The Night Spinner Soul Splinter

Soul Splinter Winter Magic

Winter Magic The Dreamsnatcher

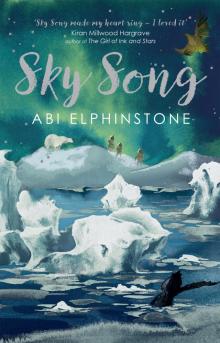

The Dreamsnatcher Sky Song

Sky Song