- Home

- Abi Elphinstone

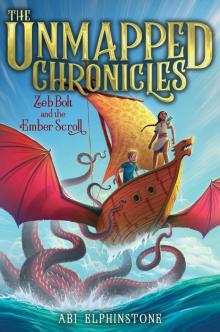

Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll

Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll Read online

For Hana Lily Suzuki

Welcome to the Unmapped Kingdoms…

Most grown-ups are far too busy to believe in magic. They have newspapers to read, bills to pay, phone calls to answer, and—most time-consuming of all—children to nag. But if grown-ups were a little less busy and a little more curious, they might notice some of the things that children see. Unlikely, impossible, extraordinary things. Like portals to secret kingdoms that reveal the truth about how our world actually began…

In case you’re wondering, it all started with an egg. An exceptionally large one. And when this egg hatched, a phoenix emerged. It wept seven tears upon realizing it was alone, and when these tears fell, the Earth’s continents were born, forming the world as you and I know it. The phoenix called these lands the Faraway, but they were dark and empty places, so, to brighten things up, the phoenix shed four of its golden feathers. And from these feathers grew secret, unmapped kingdoms, invisible to the people who would go on to live in the Faraway. These kingdoms held all the magic needed to conjure sunlight, rain, and snow, and every untold wonder behind the weather, from the music of a sunrise to the stories of a snowstorm.

Now, you may have encountered wisdom before: grandparents are wise, librarians are wise, and some (though not all) elephants are wise. A phoenix is wiser still, and this particular phoenix knew that if used selfishly, magic will grow strange and dark. But if it is used for the greater good, it can nourish an entire world and keep it turning. So the phoenix decreed that those who lived in the four Unmapped Kingdoms could enjoy all the wonders that its magic brought, but only if they worked to send some of that magic out into the Faraway so that the continents there might be filled with light and life. If the Unmappers ever stopped sharing their magic, the phoenix warned, both the Faraway and the Unmapped Kingdoms would crumble to nothing.

Next, the phoenix set about choosing rulers for these kingdoms. And being such a wise creature, the phoenix gave squabbling kings, queens, and politicians a wide berth when deciding who to appoint. Instead, the phoenix chose the Lofty Husks—magical beings all born under an eclipse and marked out from the other Unmappers on account of their wisdom, unusually long life expectancy, and terrible jokes. In each kingdom the Lofty Husks took a different form, from wizards and golden panthers to ancient elves and snow eagles, but they all ruled fairly, ensuring that every day the magic of the phoenix was passed on to the Faraway through the weather.

The four kingdoms all played different roles. Unmappers in Rumblestar collected marvels—droplets of sunlight, rain, and snow in their purest form—which dragons transported to the other three Unmapped Kingdoms. There, they were mixed with magical ink to create weather scrolls for the Faraway: sun symphonies in Crackledawn, rain paintings in Jungledrop, and snow stories in Silvercrag. Little by little, the Faraway lands came alive: plants, flowers, and trees sprang up, and so strong was the magic that eventually animals appeared and, finally, people.

The phoenix looked on from Everdark, a place so far away and out of reach that not even the Unmappers knew where it lay. But a phoenix cannot live forever. And so, after five hundred years, the first phoenix died and, as is the way with such birds, a new phoenix rose from its ashes to renew the magic in the Unmapped Kingdoms and ensure it continued to be shared with those in the Faraway.

Time passed and every five hundred years, the Unmappers learned to watch for a new phoenix rising up into the sky to refresh the Unmapped magic and herald the arrival of another era. Everyone believed things would continue this way forever.… But when you’re dealing with magic, forever is rarely straightforward. There is always someone, somewhere, who becomes greedy. And when a heart is set on stealing magic for personal gain, ancient decrees and warnings can slip quite out of mind. Such was the case with a harpy called Morg who grew jealous of the phoenix and its power.

Almost four thousand five hundred years ago, Morg cursed the nest of the phoenix on the night of the renewal of magic. No new phoenix appeared, so Morg seized the nest as her own and set about seeking to claim all the magic of the Unmapped Kingdoms for herself.

But, when things go wrong and magic goes awry, it makes room for stories with unexpected heroes and unlikely heroines. Perhaps you have heard about the girl from Crackledawn who sailed to Everdark to steal Morg’s wings, the very things that held the harpy’s power? Maybe you know about the boy named Casper who journeyed from the Faraway to Rumblestar to destroy those same wings so that the Unmapped Kingdoms and the Faraway might be saved from ruin? Possibly you have come across the Petty-Squabble twins who traveled from the Faraway to Jungledrop to find a mythical fern that banished Morg from the Unmapped Kingdoms and restored rain to our world? Or you might just be one of those wise children who sense the ways of dragons and know that they are now roaming the Unmapped Kingdoms, scattering moondust from their wings to keep what is left of the Unmapped magic turning until Morg dies and a new phoenix rises. And rise it must, because the magic is fading every day, despite the dragons’ efforts to keep it alive, and it will not be long before it vanishes altogether. For only the arrival of a phoenix can restore what Morg has destroyed and renew the kingdoms to their former glory.

There is still one story to be told, one final adventure waiting to take us to the Unmapped Kingdoms. The Petty-Squabble twins might have adventured through Jungledrop, trapped Morg in a never-ending well, and saved the world from her dark magic… but all things eventually come to an end—even never-ending wells. And from an underground world, Morg has been patiently scratching her way, ever closer, to the Faraway. She knows that if she can get ahold of the immortalized tears of the very first phoenix that fell there when our world was born, she can use their power to break back into Crackledawn, an Unmapped Kingdom she still has followers in after a visit she made there many years ago. Then she can seize control of the Unmapped Kingdoms once and for all.

Day after day, Morg has been following the pull of the phoenix-tear magic, and tonight she has reached an entrance to the Faraway. But the harpy is too weak to break the boundary into our world, so she waits in the darkness beneath an abandoned theater on Crook’s End, a dimly-lit and mostly-forgotten side street in Brooklyn, New York. Once, this street boasted a string of restaurants and lines of excited theatergoers, but as the neighborhood grew rougher and more dangerous, people moved away and the restaurants and theater closed.

No one lives on Crook’s End anymore. But all that is going to change, because an eleven-year-old boy is on the run and his feet are pounding nearer and nearer. He does not know that it is magic leading him toward this deserted street. But there cannot be phoenix tears, a harpy, and a portal to an Unmapped Kingdom close by without there being consequences.

And though Zebedee Bolt might not be the kind of child who has time for magic, it very much has time for him. Morg needs somebody to let her into the Faraway, and the Unmapped Kingdoms need somebody to kick her out once and for all. Zeb needs no one and trusts no one and that is all well and good, but trying to escape magic when you’re hurtling toward it is like trying to stop eating a doughnut when you’ve already taken the first bite. Quite impossible. You may as well just get on with it and accept that while magic throws its weight around, you’re in for a bumpy ride. Especially if that ride involves dragons rather than doughnuts, because dragons, as Zeb is about to find out, are even wilder than magic.…

Chapter 1

Zebedee Bolt was good at running away from home. He’d done it enough times, after all. And not the half-hearted wandering off that involves shouting at your parents, storming to the bottom of the garden, then slinking back in time for tea. When Zeb ran, he crossed bridges and raced through unfamiliar parks, safe in the knowledge t

hat he had memorized all the latest tricks from the Tank (a survival expert who did deeply uncomfortable things, like drink his own sweat and make rescue ropes out of his beard hair, on his television show).

But Zeb was always discovered in the end. And this was because he found it almost impossible to rein in the Outbursts. These episodes came upon him without warning and consisted of an embarrassing amount of sobbing on street corners. By the time he’d got a grip on himself, various grown-ups were usually stepping in to bring his getaway to a close.

You see, Zeb wanted to be tough. He longed to be like the Tank, who could escape any situation, like surviving weeks in the wild on a diet of grasshoppers, or emerging from a tussle with a bear with nothing but a bit of light bruising. But when you’ve got no money, a limited supply of food, and no friends to fall back on if things go wrong, it is a bit harder to remain upbeat.

So, while Zeb’s getaways always started well, it wasn’t long before the fear and panic kicked in. Where, really, was he running to? What hope was there for an eleven-year-old boy alone in New York? Who actually cared about what happened to him? Not that he ever talked about his feelings to the grown-ups who found him, the social worker in charge of him, or the foster families he’d lived with. Because talking meant trusting. And trusting other people had gone out the window years ago for Zeb.

Tonight would be different, though. Tonight he had remembered cookies. And he had made a solemn vow in front of the mirror that he wouldn’t burst into tears and get found, not even when it got dark, or a little bit scary. Because Zeb had had enough of being passed around people’s homes like an unwanted package, enough of hearing the same things whispered about him by the foster families he’d known: He’s so quiet. Why does he never smile? Is he always this moody? And, overheard this morning, from foster parents Joyce and Gerald Orderly-Queue of 56 Rightangle Row, Manhattan, while on the phone to his social worker: We’ve had him for six months now, and it’s simply not working. He doesn’t smile; he doesn’t laugh; he barely even talks! And he spends so much time shut away in his bedroom, he is almost certainly plotting something dreadful. So before he poisons us in our sleep, or worse, sprays graffiti all over the sitting room, we’d very much like to hand him back.

Their words jostled in Zeb’s ears as he ran over the Brooklyn Bridge. It was always the same thing; he was never what foster families wanted. And while the welfare agency in charge of him had placed dozens of other children in loving homes, those—like Zeb—under the care of social worker Derek Dunce hadn’t had the same luck. Derek Dunce was a buffoon of a grown-up who was capable of messing up even the simplest of things, like walking down a corridor. Finding loving families to nurture and understand vulnerable children was completely beyond him. So, like a disappointing meal in a restaurant or a faulty coat from a department store, Zeb was always sent back to the welfare agency in the end.

Zeb had crept out of Number 56 Rightangle Row for good over an hour ago, as soon as he’d gobbled down his dinner and finished talking to himself in the mirror. Now he was on the run, and though he wasn’t sure where he was running to, he kept going, even as the dark settled in and the city lights began to glitter. He pulled the hood of his jacket up, partly because he’d once seen the Tank do the same, moments before facing down a lion, and partly as a precaution. If the Orderly-Queues had sounded the alarm and the police were out looking for an eleven-year-old boy with blond hair, green eyes, and a fondness for hysterical crying, Zeb wanted to be disguised.

He turned off the bridge and hurried into the heart of Brooklyn. The place was buzzing. People poured in and out of restaurants, music sailed through open windows, and taxis honked. For a second, Zeb allowed himself to wonder what belonging to a neighborhood like this, with family and friends around him, would be like. Bike rides with a mom and a dad in the park? Weekend cinema trips with kids from school? Sleepovers at the neighbor’s house?

A longing grew inside Zeb and with it, a lump in his throat—the first sign of an Outburst. He swallowed it down, then did what the Tank did when the going got tough: some jaw clenching, followed by a grunt. Instantly, he felt better, and as he made his way on through the crowds, he reminded himself that dreaming up family and friends was pointless, because you could never count on other people. Not when they’d let you down time and time again. Humans, Zeb had come to learn, were a bit like vegetables. They claimed to be full of all sorts of good things, but ultimately, they were pretty disappointing.

According to Derek Dunce, Zeb had been born in the Bronx, his mother had died when he was only a few months old, and his father had wanted nothing to do with either of them. At first, those responsible for Zeb had hoped that the foster homes would be temporary, that he might soon be adopted into a loving family. But because Derek Dunce was entirely unqualified for his job, the foster parents Zeb had encountered were the sort of grown-ups who only really wanted uncomplicated children, the types who may throw the odd tantrum around mealtimes and get in a flap about having their toenails cut, but who generally just got on with growing up.

Zeb was not one of these children because it is hard to get on with growing up when being loved hasn’t happened first. His Outbursts led to him being labeled a “difficult child,” and at the string of schools Zeb had been to, he’d never made friends. He kept to himself, too wary to let his guard down even for a moment. It was a lonely business, but it was better than trying to make friends only to move again.

Zeb slowed to a walk as he made his way on into the city alone. He left the bustle of restaurants and bars behind him and turned onto sleepy side roads lining closed parks, until the neighborhood began to fray and become a less-visited sort of place. Zeb gripped the straps of his rucksack. This was the farthest he’d ever come by himself. He contemplated a brief sob before thinking better of it and walking on through the trail of autumn leaves.

It was quieter here—and darker. Many of the street lamps had fizzled out, and the moon was tucked behind the clouds. Zeb went on into the shadows, unknowingly drawn by the pull of magic. The streets had emptied, and now the night belonged to strays: a prowling cat, a dog hunting for scraps, and a rat scampering into the gutter.

Zeb stopped again, and the panic swelled inside him. He had pinched a sheet of tarp from the Orderly-Queues’ garage because the Tank was always talking about thinking ahead when building a shelter. But how did you know where to set up camp? Should you just curl up beneath the tarp with your cookies and hope for the best?

As if the city could sense Zeb’s unease, a breeze came out of nowhere, stirring a handful of leaves at his feet before nudging them on down the road. Zeb found himself following the leaves as they tumbled one after the other down the street and across another road.

He passed a discarded newspaper and only half registered the headlines:

GLOBAL TEMPERATURES SOAR

POLAR REGIONS MELT AT RECORD SPEED

ARCTIC ANIMALS FACE EXTINCTION

SEA SWALLOWS COASTAL TOWNS

In the last hundred years, there had been two major climate disasters. A series of hurricanes that had nearly torn the world apart, then a drought that had starved the planet of rain for months on end. And now huge chunks of polar ice were melting each day; the polar bears and beluga whales were almost extinct; the rising sea was flooding entire cities; and the hottest summer on record had seen raging wildfires across the world. Millions had lost their homes, thousands had lost their lives, and the Arctic and the Antarctic were disappearing at terrifying speeds. Everyone living in a city by the sea was nervous—everybody except Zeb. Because stopping global warming wasn’t top of his agenda tonight, or any night really. Preventing an Outburst and finding a place to hide was.

Zeb followed the leaves until they settled at the foot of a signpost that marked the start of a street so dark, it looked like the mouth of a cave. Zeb felt his knees wobble and a familiar lump slide into his throat. To prevent an episode of uncontrollable howling, he puffed out his chest, raised his chin,

and focused on the fact that there was nothing and nobody waiting for him if he let an Outburst loose now. Joyce and Gerald Orderly-Queue had shown more affection for the Saturday crossword than for him. He had to go on. He had to start a new life on his own.

He looked up at the street sign. It was rusted at the hinges and the lettering was chipped, but he could just make out the words.

“Crook’s End,” he murmured.

He took a small step closer. There were more signs nailed to the buildings: PABLO’S PIZZAS, PASTA HEAVEN, BROOKLYN BURGERS. But these restaurants looked like they’d been boarded up for a while now, and at the end of the street, closing the road off into a dead end, was another building. It was taller and wider than the others, and the stonework above the old wooden door was a little fancier.

Zeb glanced at the faded sign hanging above the door: THE CHANDELIER, it read, and beneath it was a list of what appeared to be outdated showtimes.

“A theater,” Zeb whispered. “All the way out here.” He eyed the door, which had been padlocked shut. “Grown-ups, they always focus on the doors.…”

But Zeb knew, from personal experience, that if you could escape a building in a number of ways: out of a window, via a skylight, down a fire escape—then there were multiple points of entry, too.

He settled for a ground floor window now, one covered with planks that had rotted through. He pulled them away to find a grubby pane of glass, and he hadn’t expected to see much when he pressed his face up against it. But at that precise moment, the moon edged out from behind a cloud. And because the roof of the theater was in need of repair, the moonlight slipped in through the cracks and shimmered on the most enormous chandelier Zeb had ever seen. Hundreds of glass droplets hung from the domed ceiling, glinting silver like a giant’s crown.

The moonlight was so bright that Zeb could see quite clearly inside now. Beyond a tiny foyer, the theater opened to reveal a balcony of seats up high, and down on the floor, more seats arranged in rows and draped in cobwebs. These led up to a stage fringed by tattered curtains and covered in dust. The stage was empty but for one thing. And when Zeb saw what it was, a small smile escaped his lips.

Everdark

Everdark Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll

Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll Rumblestar

Rumblestar Jungledrop

Jungledrop The Night Spinner

The Night Spinner Soul Splinter

Soul Splinter Winter Magic

Winter Magic The Dreamsnatcher

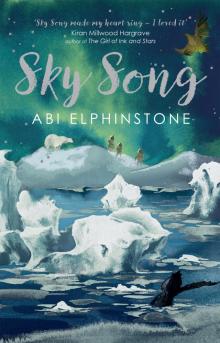

The Dreamsnatcher Sky Song

Sky Song