- Home

- Abi Elphinstone

Winter Magic Page 3

Winter Magic Read online

Page 3

5

There was a moment. A stillness. No one moved. Then Eddie turned too fast; his feet skidded underneath him. Maya caught hold of the back of his coat. But the man was pulling against her again.

‘Get off him!’ she cried.

The man dug his heels in. ‘Come quietly, Eddie,’ he said through gritted teeth. ‘Let’s not make a fuss.’

Eddie tried to twist free. There was still a bit of fight in him, but he was too weak to struggle hard. Blocking the man with her whole body, Maya matched his every scratch, every kick with one of her own. She had a duty to Eddie. A loyalty. And not just because of the shilling he’d given her so she could get onto the ice in the first place. It felt more than that now. She wasn’t going to give up easily.

‘Leave him alone! Get off him!’ she yelled.

The man shoved her aside with a sweep of his arm. She staggered a little, then launched herself at him again.

‘I’m warning you. Keep out of this, girl,’ the man spat. ‘This is a private concern.’

‘You can’t shut him away again. He’s sick, that’s all. He needs a doctor!’

All at once there was a tearing sound. The cloth of Eddie’s coat gave way. It sent Maya wheeling backwards. And sent Eddie forward, straight into his captor’s grasp. Before Maya could regain her balance, the man had whisked Eddie out of sight.

‘Stop him! He’s kidnapping Eddie! Don’t let them get away!’ Maya screeched. A few people stared at her oddly. But most bustled on past, too caught up in the delights of the frost fair to notice her distress.

Frantic, and on tiptoe, she tried to see where the man and Eddie had gone. It was as if they’d vanished into thin air. She asked stallholders, sellers, random passers-by, but no one had seen them. No one seemed to care much, either. People were still whooping in the swingboats, still buying gingerbread. Maya clenched her fists. How could they carry on as normal? How could they not want to help?

She didn’t know what to do next.

Determined not to cry, Maya headed in the direction of the riverbank. She’d suddenly lost heart in the frost fair. Nothing would be any fun without Eddie to share it with. And just when she’d been getting to know him, too. It all felt really unfair.

But, she thought darkly, there was still plenty she didn’t know about Eddie. Despite her first impressions, he hadn’t seemed the slightest bit mad. He was just someone who wanted to have fun. So why had he been locked away? Where was it that he’d escaped from? And who was that creepy man who’d snatched him back again?

Her bottom lip trembled just thinking of the awfulness of it all. She’d tried to help Eddie, really she had. Trouble was, she wanted to do more, but how could she when he’d disappeared?

Beneath her feet, the ice had turned grainy. Water seeped into her socks so when she walked it made a squelching sound. She was tired. Wrung out. Whatever this experience was, she’d had enough of it. That great sense of purpose she’d felt walking over London Bridge had gone. Without Eddie, she didn’t see the point in being here. Time travel, she decided, was even less fun than real-life travel. She was ready to go back to the present.

Yet Maya wasn’t sure how this part of things worked. Everything had started on London Bridge, so she decided to head back there, hoping this time the taxi would prove easier to find. It was as good an idea as any. But what if the taxi wasn’t there? What if she was stuck in the past for good?

Climbing the steps up off the river, she took a deep breath to slow her whirling brain. The air smelled different – not of cold any more, but of the city starting to warm up, like old, forgotten fruit at the bottom of her school bag. It had started to rain. Turning up her coat collar, she hurried on.

The shouting didn’t register at first. It was coming from a side street somewhere to her right. As she approached, it got louder. She could just about make out the words.

‘I won’t go inside again! I won’t!’

With a jolt, Maya recognized the voice. She also knew the dark, spindly outline of a boy in a flapping coat, wrestling with someone on the pavement.

‘Let go of me!’

‘Quiet!’ said the man. ‘Enough of this ridiculous noise!’

Maya gasped in relief. She raced down the street towards him. ‘Eddie!’

At the sound of Maya’s voice, he looked round. The tiniest distraction was all it took. In one sly move, the man grabbed Eddie’s arms and bundled him up the steps and inside. Just as she reached the building, the front door slammed shut. As she bounded up the steps, she heard a key grind in the lock.

‘Eddie? I’ll get you out of there somehow. Don’t worry. I’m here.’

No answer.

She banged her fists against the door. ‘Hello? Eddie? Are you all right?’

There was no reply. The door stayed smugly shut.

Eventually, she backed down the steps and gazed up at the house – for that’s what it was, a house. She was surprised by how ordinary it looked, with two front windows on each floor and chimneys in the roof. It wasn’t how she’d imagined a prison to be.

She went to the door again and thumped on it.

‘I’m not going away until this door is unlocked. I’ll stay here all night if I have to!’ she yelled.

A little way along the street an upstairs window slid open. A lantern appeared, followed by woman’s white-capped head.

‘You won’t be keeping up this hollering till morning, will you?’

Maya stared at the woman.

‘Because we all need our sleep, my dear – your friend Eddie especially.’

‘Eddie’s been kidnapped! We have to do something!’ How could she worry about sleep? Maya wondered. Shouldn’t she be contacting the police?

But the woman actually laughed. ‘Kidnapped? Good gracious! Why on earth would you think that?’

Maya folded her arms. This woman had no idea, did she? She lived next door and didn’t have a clue what had been going on.

‘He told me . . . he’s being kept prisoner!’

‘My dear,’ the woman said patiently. ‘Poor Eddie doesn’t like being kept inside, but it’s doctor’s orders.’

Maya didn’t understand. ‘Doctor’s orders? He said this place was a prison.’

‘Indeed, it probably does feel like a prison to him.’

‘But the man who came after him,’ said Maya, shaking her head. ‘Eddie said he’d stop at nothing to get him back.’

The woman sighed. ‘That was Eddie’s father, my dear.’

‘His . . . what?’

Now Maya was confused. Very confused. That man in the black cloak hadn’t looked very fatherly. He hadn’t acted it, either.

‘His father,’ the woman repeated. ‘He’s at his wits’ end. Eddie won’t accept how ill he really is.’

‘Hang on.’ It was getting hard to keep up. ‘So he’s ill? I know he’s got a bad cough, but—’

‘Yes,’ the woman cut in. ‘He’s very sick. A congestion of the lungs, so they say.’

Mixed with her relief for Eddie, Maya felt a sinking dread. Eddie hadn’t been kidnapped after all – not properly. But this business with his lungs sounded pretty bad.

She had a feeling the woman wanted to keep talking. There were neighbours of Gran’s like that, who sucked up bad news like vampires. But there wasn’t anything left to say. Then, suddenly, Maya had an idea.

‘Have you got a pen?’ she asked.

The woman pulled a face. ‘You’ll be wanting the inkstand too, will you?’

‘A pencil, then. And some paper, please?’

Moments later, both dropped from the window to land on the pavement beside her. Using her leg to rest on, Maya scribbled a note – not to Eddie, but to the man who was his dad. She thought it might be harder to ignore than a knock at the door, and it was the one thing she could think of that might help.

In the note, she tried hard to be polite and persuasive, but the best line was Eddie’s own: ‘People need freedom to breathe,’ he’d said to he

r. Now it was his dad’s turn to hear it.

Once the note was posted through Eddie’s door, it really was time to go home.

Joining the main road again, Maya headed towards London Bridge. The rain was falling harder; her hair hung limp around her face. At least no one could tell that she was crying.

What made it sadder was the fun she’d had with Eddie. It was such a waste to spend what time he had locked away inside a house. It was as if his father’s own worries were more important than Eddie’s happiness. She just hoped he’d at least read her note. And this made her sad for Gran, too, stuck in her horrid care home because Dad thought she couldn’t cope. The more Maya walked, she more she began to see the similarities.

Down on the river, the crowds were coming off the ice, moving almost with the same speed they’d gone on it. The frost fair was being dismantled. Tents were folded, baskets packed. The stallholders hurried to the river’s edge with whatever they could carry – swingboats, terriers, trays of gingerbread.

‘Quickly! The cracks are growing!’ someone shouted.

Once again, Maya found herself deep in the crowd; she let herself be carried along the road. The rain, falling in great curtains, turned the cobbles from white to slushy grey. By the time she reached the stone archway that led onto London Bridge, she was soaked through.

Pushing back her wet hair, she braced herself. The bridge, as before, was heaving with people. But this time, instead of barging into her, they seemed to melt away.

The rain – great droplets of it – started dancing before her eyes. A hush fell across the whole bridge. Everything went still. Only Maya’s feet kept moving, beating out a rhythm on the cobbles as she walked. Up ahead, she saw two red lights glowing through the rain. It took her a moment to realize what they were.

The taxi sat in traffic with its engine running. It was her taxi – she recognized the adverts for West End shows all along its sides, and almost cried out with relief. Climbing in, she flopped down exhausted on the back seat.

‘Ouch,’ she muttered, as something hard dug into her hip. Her hand went to her coat pocket. Inside was the funny brown lump Gran had given her, right where she’d left it. Yet it definitely hadn’t been there at the frost fair. And if it had fallen out here in the taxi, then how on earth did it get back in her pocket again?

She’d no idea – about any of it.

‘A really weird thing’s happened,’ Maya began. Then, seeing her father and sister, she stopped. Jasmine, eyes shut, was listening to her music. She hadn’t moved an inch. Nor had the taxi. The same song was playing on the radio. And Dad was still talking to the driver. Maya’s hair was dry, her trainers no longer squelchy-wet.

These things definitely didn’t happen in dreams

All she had to show for her adventure was the pencil Eddie’s neighbour had lent her. It was still in her other pocket; she’d forgotten to give it back. Her family hadn’t noticed she’d gone. She hadn’t actually been gone, which made things more complicated and – strangely – easier.

6

Back home in Brighton, Maya went straight to her room, closing the door behind her. She wanted a quiet moment to think. There was a buzzing in her head, like she’d been standing too near the sound system at a party. She still didn’t understand what had happened. But somehow, Gran’s present had played a very big part in it.

Taking it from her pocket, Maya looked at it again. The unwrapped brown end of it was, she saw, old gingerbread. Even the shape of it was similar to the great slab Eddie had bought. The paper around it was tatty: as Maya held it up to the light for a proper look, she noticed something written on it. Immediately, she pictured Eddie at the frost fair, pen in hand, and her skin began to tingle. Though the ink was faded, she could just about make out the words:

This piece of gingerbread was bought at the Frost Fair on the Thames, 5th February 1788, by Edmund Mullig—

Edmund.

Her hunch was right. The ‘Mulligan’ part of his name was almost there, too.

So there really was a link.

No wonder Eddie looked a bit familiar. Thinking back on it, his eyes crinkled up just like Gran’s when he smiled. And that strong bond she’d felt with him – well, that was family, wasn’t it? He’d trusted her to help him when he was desperate, just as Gran was reaching out to her now. How could she ever have been jealous of Jasmine’s brooch? This piece of gingerbread meant more than all the brooches in the world.

She had to speak to Gran right away.

Maya’s mobile was out of credit. She raced downstairs for the landline phone. Dad was skyping Mum in India, and out in the kitchen Jasmine was banging around, making supper. The coast was clear. Once back in her room, Maya picked up Gran’s present. Her skin did that tingly thing again.

Sitting on the floor, her back against the door, Maya dialled directory enquiries for the number to Gran’s care home. That part was easy. Getting put through to Gran in person was a whole lot harder.

‘Who?’ the receptionist kept saying. ‘Mrs who?’ There were clicks and crackles on the line and muffled voices in the background, until finally, she got Gran herself.

‘Have you asked your father if you can use the phone?’ Gran barked on hearing Maya’s voice.

‘Gran,’ said Maya, trying to stay patient. ‘I’m not five any more. Now listen, it’s about that present you gave me today.’

‘Edmund’s gingerbread?’

‘Yes, Eddie . . . I mean . . . Edmund.’ It felt funny to call him that. ‘Can you tell me some more about him?’

‘I’m tired,’ said Gran tartly. But Maya knew she was just testing her out, seeing how much she really wanted to hear about the person no one else believed existed.

So Maya tried again. ‘That thing you said today about the world being full of stuff we don’t understand – well, I took your advice and went looking for it.’

She heard the hesitation.

‘You did?’ Gran’s voice sounded strangely small.

‘I did.’

Another pause, then Gran simply said, ‘Good.’ And neither of them had to explain themselves. They had an understanding: that was all they needed.

‘The present was wrapped in blue paper, and it’s got writing on it,’ Maya went on. ‘It says Edmund’s full name. He was a Mulligan, wasn’t he?’

‘He was.’

‘And he was alive in 1788 because he bought this piece of gingerbread.’ And I saw it happen, Maya thought.

Gran sighed wearily. ‘Poor Edmund. He was my father’s great-great-great-grandfather – too far back for anyone to remember much about him. But somehow that piece of gingerbread survived and got passed down through our family. No one really wanted it, but it fascinated me. So I did a bit of research into Edmund Mulli—’

‘How?’ Maya interrupted. She couldn’t imagine Gran browsing the internet. Then she remembered something Gran had said earlier. It sent a shiver of excitement down her neck. ‘You met him on your travels, didn’t you? You said so this afternoon.’

Though Gran was pretty old, she’d not been alive in 1788. It meant one thing: Gran must’ve time-travelled, too. But if she had, then she wasn’t about to discuss it. A prickly silence was the only answer she’d give to her granddaughter’s question. And Maya, who didn’t quite know how to ask more directly, had to leave it at that.

‘I’ll tell you this, though,’ Gran said. ‘He was mollycoddled terribly by his family. They never let him do anything – go outside, see friends, anything – especially after he got ill. Something to do with his lungs.’

Maya nodded. Gran’s memory was working – this was just how the neighbour had explained things.

‘Did he . . .’ She cleared her throat nervously. ‘Did Eddie die?’

‘Of course he did – dear, dear me.’ Maya heard the smile in Gran’s voice. ‘But not in 1788.’

Her stomach did a swoop of relief. ‘So what happened?’

‘Eventually, his father realized that shutting him away sim

ply made his health worse. You see, he wasn’t just going to give up and be an invalid. He kept on escaping from the house and going on wild capers across London.’

Maya grinned down the phone. She could absolutely imagine Eddie doing this, and it was so brilliant to hear it from Gran.

‘The final straw was when he escaped the house to go to a frost fair on the river. It was all very public, catching him and bringing him home again, and someone wrote a letter to the family, begging that they reconsider their treatment of him.’

‘Really?’ Maya gulped. ‘Did it work?’

‘Amazingly, it did. Soon after, they stopped all the bed rest, the pandering, the weak tea and lean meat diet. And what do you know? Eddie got better. He lived to a good age in the end, made happier by living it in the way he wanted.’

A lump grew in Maya’s throat. So things had all ended well for Eddie after all. ‘I’m so glad,’ she said, her voice thick with tears.

Maya leaned her tired head against the door. So that was Eddie’s story; Gran’s story, though, felt like it hadn’t ended yet.

In the background, she heard another woman’s voice. She was telling Gran it was too late to be on the phone.

‘We have rules in here, Mrs Mulligan . . .’

Maya didn’t catch the rest. Suddenly, it sounded like Gran was pressing the phone right against her mouth.

‘People need their freedom, Maya. They need to breathe,’ Gran whispered.

The line went dead.

Maya stared at the phone in her hand, her heart suddenly pounding. Those words were Eddie’s words. She’d borrowed them herself to write that note, and now Gran was using them, too. She glanced at the gingerbread, still there in her other hand. It had made its way through the Mulligan family in pretty good shape for a 200-year-old piece of cake. So had those words. They were, Maya realized, a sort of souvenir themselves. They meant something.

And that something was Gran.

She wasn’t going to be happy in her care home. She’d hate being told when to take her phone calls, and everything else. She needed to breathe.

I’ll speak to Dad in the morning, Maya decided.

Everdark

Everdark Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll

Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll Rumblestar

Rumblestar Jungledrop

Jungledrop The Night Spinner

The Night Spinner Soul Splinter

Soul Splinter Winter Magic

Winter Magic The Dreamsnatcher

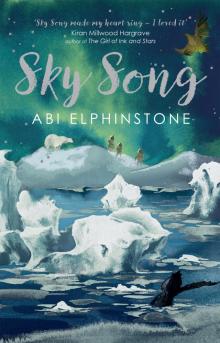

The Dreamsnatcher Sky Song

Sky Song