- Home

- Abi Elphinstone

The Dreamsnatcher Page 2

The Dreamsnatcher Read online

Page 2

Moll swallowed again as they stepped out of the glade back into the trees. Then Gryff tensed. Hanging from another branch by a piece of tattered string was an owl: dead, eyeless.

‘Just an owl,’ Moll whispered to herself.

But she knew the signs; every gypsy did. Caged bones. Dead rats. Hanging owls. These were witch doctor omens. She and Siddy had laughed at the stories of Skull being a witch doctor, but Oak had been telling the truth all along. And if Oak knew the truth about Skull no wonder Skull’s gang wanted to force Oak’s camp out of the forest.

Moll glanced behind her; it wasn’t too late to turn around. But Jinx . . . She couldn’t leave Jinx in a place like this. She clenched her teeth.

Then the whispering started.

It was a strange kind of whispering – scratched and guttural, like muttering – as if it was coming from deep within someone, right from the back of their throat.

And it was close, too close.

Moll’s body stiffened and fear settled around her neck. And yet she edged closer, somehow drawn to it. Gryff followed. It was louder now and there was a rhythm to it – strong and pulsing. And slowly, like a frosty breath, a feeling slunk into Moll’s mind. There was something familiar about those whisperings. The feeling lingered in her mind, breathing quietly.

Then a movement caught her eye. Cloaked figures were stirring between the trees. She edged closer still, hiding behind a tree, and there, just in front of her, was Skull’s camp. Four figures were circling a fire in the clearing, moving like a dark wave.

Moll’s breath caught in her throat. The whisperings were getting louder and faster now, growing like an untamed wind. And they were words that didn’t belong to Moll’s world: strange, rasping words that—

The thud of a drum.

The hiss of a rattle.

Moll’s blood froze. Her nightmare was unfolding before her.

She was so close that the drumbeats thudded through her body and the rattle hissed in her ears. Gryff was absolutely still beside her, his eyes locked on to the cloaked figures. They were moving faster now, a whirl of faceless black. But there was one figure who wasn’t stirring; instead he squatted by the fire like an enormous spider, making something from a ball of wax.

Suddenly the figures stopped, their heads bent, the drum and rattle silenced.

Unfolding his body, the squatting figure stood upright. Firelight fell upon his face which was hidden completely by a white mask. A shiver tore through Moll’s body. And then a horrible feeling seeped into her. She’d seen that mask before, heard that drum and rattle, not just locked inside her nightmare, but outside it too – in real life.

The mask was white and it shone in the firelight like polished bone. Dark holes marked the eyes and two lines of jagged bones jutted out below in a grim smile. Moll knew right away that this was Skull, his mask a sign of the witch doctor’s name. And, although Moll could see the mask had been carved from wood then painted white, it shone out with all the horrifying sickness of a skull.

Skull held up the wax, now moulded into a shape: the unmistakable outline of a person. The chant began to grow again, pulsing in time with the drum and the rattle, and an eerie coldness rippled through Moll. Skull raised the wax figure into the air and squeezed it in a clenched fist. The wax, still warm, squirmed between his fingers like glue.

Moll felt the breath drain from her body, as if an iron fist was crushing her lungs. Beside her, Gryff shivered. A laugh slid out between Skull’s teeth, coiling its way between the trees. The chanting rose and once more Skull gripped the small figure, punching his fist into the air. The wax squeezed through his fingers until it was a mangled lump once more.

Then Skull’s voice came, slithering and cold, seeking them out like a chill. ‘Come, beast, come, child. Come, beast, come, child . . .’

Moll felt it, as if he’d called them by their names. The chant was for her and Gryff. She was sure of it. But stranger than all of that was the feeling growing inside Moll. She almost wanted to step forward into the clearing towards Skull. She clutched at her talisman.

‘Keep me safe,’ she murmured. ‘Keep me safe.’

Then a horse brayed, snapping her from her trance. She drew breath sharply and staggered backwards.

‘Jinx . . .’

She knelt down by Gryff, but he stared ahead, his body shaking, as if the chant was holding him prisoner.

Moll’s heart raced. ‘Come on, Gryff!’ she whispered.

Gryff jerked his head back behind the tree. His eyes were wild and his hackles wet with sweat.

Moll breathed deeply. ‘Skull – he’s – he’s calling me – he’s calling us both! We’ve got to move!’

She scanned the trees around the clearing, trying to block the chant from her head. To her right, beyond the fire and battered wagons, was a canvas tent propped up against a tree. Gryff skirted round towards it and Moll followed. Behind the tent was a huddle of larger shapes and she’d know those silhouettes anywhere: they were gypsy cobs.

Like a shaking fledgling, Moll pressed her body into the trees, and Gryff slunk through the shadows beside her. They crept past the canvas tent and there, just metres away, was Jinx.

She was easy to spot – smaller than the rest of the cobs – her palomino coat glowing in the darkness. And she was edging forward in tiny, fragmented steps, her eyes wide with fear. Moll’s heart hammered. Had Jinx seen her? Her halter was still on and her tethering rope trailed on the ground. Why hadn’t they tied her up? Why hadn’t she run off? Moll tiptoed forward until she was behind the closest tree, clutching her catapult tight.

She stopped sharp. Jinx wasn’t coming towards her; she hadn’t even seen Moll. Emerging from the shadows, just metres in front of the tree Moll was hiding behind, was a boy. And he was tiptoeing towards Jinx with his hand outstretched. He was taller than Moll, with a tattered waistcoat and a faded blue shirt stained with saddle polish and dirt. But he looked about her age – twelve, thirteen at most.

Moll frowned and squinted at the boy through the darkness. He was no gypsy . . . He had fair hair and a pale complexion. What was an ordinary boy doing in Skull’s camp? And yet beneath the scruffy blond hair was a bright feather earring, blue and black striped. Only one type of person wore a jay feather earring: a Romany gypsy.

A ball of jealously grew within Moll; Jinx was her cob and this boy was beckoning her. And he had no right.

Jinx paused, her ears pricked, her tail stiff. She looked straight at Moll whose heart quickened. Jinx had seen her but the boy hadn’t realised.

‘Here, girl, come on then, a little more,’ he urged, taking a step closer in his scuffed leather boots. He stretched out his hand as far as it would go. ‘I’m not going to hurt you.’

His voice was softer than Moll had expected and she could hear the pieces of carrot turning over in his hand. But Jinx was no longer interested because she knew that Moll had come for her.

Like a shadow to the unknowing boy, Moll raised her own hands. But they were not filled with carrots; they were clasping the catapult. Gryff crouched low beside her – ready, like a hunter. The pebble was in the pouch and she raised it to her chin. Closing one eye, she placed her thumb on the Y-frame and pulled back. The rubber strips stretched until taut and then she took aim at the back of the boy’s head.

Everything was still beneath the chanting.

For a second, Moll wavered. She’d never used her catapult on a person before. There were rules back in the Ancientwood. But Skull’s camp was a place without rules and she needed to get away, fast.

She drew the pouch back, a notch further.

Then fired.

The boy doubled over in pain, clutching the back of his head. ‘Argh!’

In the next fraction of a second, Moll was charging towards Jinx.

‘Argh!’ the boy yelled again, rocking his head in his hands. He struggled up in disbelief. ‘Skull! There’s – there’s someone here!’

He staggered to a tree, unable to piece tog

ether what was happening. Moll grabbed hold of Jinx’s mane and leapt up on to her back. Digging her heels into the cob’s flanks, she spurred Jinx on.

The chanting had stopped and the camp was silent.

‘It’s a girl!’ the boy cried behind her. ‘And a button-sized one at that!’

There were a few guffaws from the fire.

Then a voice, cold and loaded: ‘After her, Alfie.’

Guiding Jinx with only her legs and voice, Moll urged the cob on, away from Skull’s camp.

‘Go, Jinx, go! Faster than you’ve ever run before!’ she cried. It didn’t matter that her nightmare had come alive any more. Now it was just about the chase – and she had to win.

If the boy was in pain, he no longer showed it. Placing his fingers to his mouth, he whistled. The smouldering body of a black stallion cob appeared from behind a tree, its eyes as dark as night, its nostrils steaming. Yanking the tethering rope from the cob’s halter, the boy hoisted himself up on to its back.

‘After them, Raven!’ he yelled, kicking hard.

Weaving between trunks and dipping beneath branches, Moll raced back towards the glade – past the giant cage, past the rat, past the owl, leaving all of that behind. Jinx’s neck was stretching forward now as she darted between the trees, reaching the full speed of her gallop. And every now and again Moll glimpsed a flash of grey and black stripes as Gryff ran alongside them.

‘That’s my girl! Go on, Jinx! Go on!’

But there was a thundering of hooves behind her now, churning up the deadened glade. Moll twisted her head for a second. The boy was there, some metres behind, on his stallion cob. Whoever he was, he rode fast.

‘Go on, Jinx!’ Moll urged.

The boy and his stallion, Raven, continued to gain on them. Moments later, they were side by side and the boy was crouching up on his feet on Raven’s back, ready to leap towards Moll. His eyes were blue and intense, like his jay feather, and his teeth were set. Moll’s eyes widened and she kicked harder.

The boy steadied himself, about to leap, but Moll leant forward, pulling Jinx’s halter hard. They sidestepped his grasp and, from somewhere nearby, Gryff growled.

The boy looked around – alert, on edge – but there was nothing there, only dawn needling through the darkness, pricking the night sky blue. The boy slid back to a seated position, cautious now.

Moll breathed again. ‘Just to the river, Jinx. We’re safe past there!’

‘Come back here, titch!’ the boy yelled, spurring Raven on.

Moll scowled, her face hot with fury at the insult. She leant forward towards Jinx’s ears. ‘That’s my girl. Keep going, Jinx!’ They leapt over stumps of trees and fallen branches. On, on, towards the river.

‘You thieved from us, spudmucker!’ Moll cried over her shoulder. ‘I’m taking back what’s rightfully ours! Oak’s camp is never leaving the forest, however hard you try to force us out!’

Jinx galloped even faster, but the thunder of hooves behind them didn’t stop. Like cogs in a monstrous machine, they charged on, closer and closer.

‘You wait till Skull gets his hands on your scrawny neck!’ the boy shouted.

Foam was dripping from Raven’s mouth, flecking his chest white. Again the boy crouched on the cob’s back, swinging for Moll’s halter. But Jinx burst away. The river was in sight, sparkling in the moonlight like a promise. Moll leant forward and stroked the soft, downy hair behind Jinx’s ear, the place where sensitive cobs keep their souls. They were within strides of the water, racing towards the alder trees.

‘Now, Jinx, jump!’

Jinx lifted from the ground, knees bent, hooves tucked beneath her stomach. They soared across the river and landed, panting, on the other side.

Moll bent low to Jinx, whispered in her ear and, as Jinx surged forward, Moll leapt from her back into the branches of an alder overhanging the river. She scampered upwards as Jinx’s hooves faded towards the clearing of the camp.

On the other side of the river, Raven came to a skittering halt. He paced by the bank in tight circles. And, from beneath a mop of fair hair, his rider cursed.

Safe in her aerial world of branches and leaves, Moll glowered down.

‘One shout from my pipes and the whole camp’ll come running,’ she hissed. ‘The Ancientwood is Oak’s territory so you can go back to your den of thieves and wipe your backside on a tree root!’ She drew out her catapult and brandished it at the boy. ‘And they say girls can’t fight!’

The boy scowled. His cheeks were flushed and he was breathing fast.

Moll crouched in the tree, tucking her feet into its branches. ‘You’ve no right here; beat it.’ She looked Raven up and down, then spat through the leaves. ‘Your cob is nothing in a race with Jinx!’

The boy’s body stiffened. ‘Don’t you insult Raven,’ he replied, stroking the stallion’s mane. ‘You saw how he outdid your pony in our glade. Raven would win a gallop and you know it!’

‘Pony?’ Moll cried, leaping up a branch and hissing. ‘Jinx isn’t a pony! She’s quick as lightning!’ She paused. ‘You’re daft, you are. Tree spirits have eaten your brains.’ She picked at a leaf casually. ‘I’ve also got a wildcat,’ she said, ‘and you’re not going to top that.’

At the mention of the wildcat, the boy shifted on Raven and then went very, very still. His eyes narrowed.

Somewhere nearby Gryff growled, low and deep, like the groaning of a faraway glacier. And suddenly Moll felt as if she’d betrayed a terrible secret. She coiled her body into the alder and scuttled further up its branches.

The boy’s face relaxed slightly. ‘A wildcat?’ Then he scoffed. ‘Raven’s one of the only animals who can recognise himself outright in a mirror. Beats an imaginary wildcat.’

But there was something about the boy’s voice now. Something which made the hairs on Moll’s arms stand on end.

Again Gryff’s growl came, even deeper than before, warning her to stay back. But why? There was no drum, no mask, no chant now – only the rippling of the river winding downstream. Skull was far away in the Deepwood and this was just a boy. Not even a real gypsy boy if his colouring was anything to go by.

The boy turned away, tugging at Raven’s halter and gripping his talisman, a knot of his cob’s black hair tied to a string round his neck. Moll remained silent, watching them leave. And then, nonchalantly, she slipped backwards, catching her knees on the branch so that she was hanging upside down above the water.

‘And don’t come back!’ she shouted.

A sickening lump formed in her throat; the boy and his cob were coming back. The boy was kicking Raven in the flanks, hard, and they were charging back towards the river. Towards her.

Moll flipped her body back into the tree. She’d have to jump, then sprint to the camp to get there first. She gasped. Her foot was caught, jammed between two branches. She couldn’t move, couldn’t breathe. And the boy was charging towards her, just metres from the bank.

There was a rustling from the undergrowth beneath her as, like a ripple of silk, Gryff sprang up into the branches, pounding at the one that trapped Moll’s leg. And when that didn’t work . . . he touched her. For the very first time. Actually touched her. She felt his soft, warm strength pushing against her, and it filled her with courage. She yanked her foot harder and harder until it slipped free. Then she leapt to the ground, landing in a crouch, and sprinted several paces away from the river. She turned.

Gryff was still in the branches, hissing, growling and stamping his forelimbs. His eyes glowed green and his hackles rose, as if he was growing in size, and, as he snarled, he bared rows of white fanged teeth.

The boy yanked Raven’s halter and they skidded to a halt, centimetres from the riverbank. The soil beneath Raven’s hooves began to crumble and they retreated backwards.

The boy stared at Gryff, blinking in disbelief. His voice was altogether different now: half curious, half afraid. ‘It – it can’t be . . .’ he stammered. ‘The beast – the child from . .

.’ He looked Moll straight in the eye.

But at that second a hand clapped down on Moll’s shoulder.

The boy turned sharply, then galloped back into the Deepwood.

And Moll whirled round to face Oak.

Oak didn’t ask where she’d been; he could tell from the look on Moll’s face: guilt mingled with fear. She’d crossed the boundary into Skull’s camp – that much was clear.

Oak pulled a chair round to the foot of Moll’s wooden box bed, brushing the red velvet curtains wide. Oak was a strong, sturdy man, but, as he ran a hand over his stubbled jaw, Moll saw that he looked tired. She glanced at his large gold ring set with obsidian stone – the mark of his role as head of the camp. It glowed under the lamplight and a flicker of guilt wavered inside Moll. She looked away and focused on her wagon: at the stove with its shiny copper pans, at the pinafores strewn on the pine floor and at the small wardrobe with gigantic fir cones and kingfisher feathers scattered on its top.

Oak sat forward, fiddling with his talisman, a lump of coal in a leather pouch he kept in the pocket of his waistcoat. But he didn’t speak yet. He had his ways.

Moll pushed her patchwork quilt back to her knees. ‘I got Jinx back, Oak. I did it – all by my unhelped self.’ A look of pride, of wilful defiance, flashed in her eyes.

Oak looked up. ‘Jinx isn’t important, Moll. Not important like you . . .’ He shook his head. ‘Domino – my own son – he should’ve known better than to fall asleep on watch. Anything could’ve happened.’

‘But – but I was saving Jinx from certain death over there!’

Oak shook his head. ‘You disobeyed me, Moll. After everything you promised.’

Moll thought fast. ‘Blame that blinking nightmare! Pulled me right over the river into the Deepwood this time.’ Oak said nothing and Moll could tell he’d sensed her lie. She dodged his eyes. ‘Well, at least I made the most of it – and I proved fair and square to Florence and the others that I’m no outsider.’

Everdark

Everdark Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll

Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll Rumblestar

Rumblestar Jungledrop

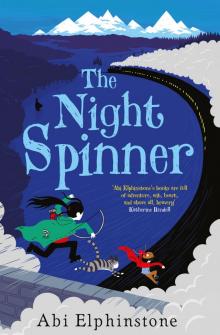

Jungledrop The Night Spinner

The Night Spinner Soul Splinter

Soul Splinter Winter Magic

Winter Magic The Dreamsnatcher

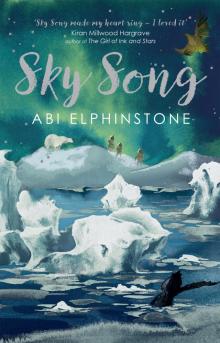

The Dreamsnatcher Sky Song

Sky Song