- Home

- Abi Elphinstone

Jungledrop Page 2

Jungledrop Read online

Page 2

Fox had concluded some years ago that her obvious lack of talent was what made her unlovable to her parents. Stamping on other people’s feelings every day was all very well – after all, Fox didn’t fancy being kind because being weak, as well as talentless, would only add to her misery – but the heart is a fragile thing and sometimes people assume that the best way to keep theirs safe is to build a wall round it. And that was just what Fox had done. Hers was a very high wall that had grown up over the years without her truly realising, because it made dealing with being unlovable ever so slightly easier.

She stole a look at Fibber. Was he quieter than usual because he had, finally – and perhaps predictably – come up with a way to save the family fortune? Maybe he was just moments away from announcing his triumph. Fox contemplated her options. She could pin Fibber down, snatch his business plan, then – she thought fast – eat it? Or was it time to do a Great Uncle Rudolph (without the tunnel drama): grab the plan and hold it hostage until Fibber agreed to say that he and Fox had come up with all the ideas together?

Before Fox could do either, the door to the penthouse suite opened. In stormed Gertrude Petty-Squabble, wearing a white bathrobe, white slippers and a white towel twisted up over her hair. She was wearing so much white she looked uncannily like a meringue while behind her, red-haired and red-faced, was Bernard Petty-Squabble resembling a volcano rammed into a business suit.

Bernard flung the door shut. Then he and his wife eyed their children with the kind of look that is usually only reserved for traffic wardens and large spiders. Fox gulped. She knew all too well that when her parents barged into a room like this it was never good news…

‘The facial was a disaster,’ Gertrude snapped.

She swept across the living room, plucked a grape from the fruit bowl on the table between the twins, threw it in her mouth, winced and then spat it out onto the carpet.

‘Just as the beautician was finishing up,’ she muttered, ‘I launched into my sales pitch for the new Petty Pampering range whereupon I was told that the spa had decided to discontinue stocking my products, as of next month, because of complaints about the moisturiser.’

Bernard rolled his eyes. ‘I knew that moisturiser would come back to haunt you. But did you listen to me?’ He thumped his clipboard down on the table. ‘No. Too busy waiting for your son to sweep in and save the day.’

Fibber shifted but didn’t look up.

‘Time is marching on,’ Bernard tutted to his wife, ‘and Petty Pampering profits are accelerating at the pace of an asthmatic ant.’

‘While Squabble Sauces,’ Gertrude shot back, ‘are run by a man with about as much skill as a newly born baboon.’ Before her husband could reply, Gertrude rounded on Fibber. ‘I thought you said we’d discontinued the moisturiser because it dyed customers’ eyebrows green?’

Fox watched Fibber, every muscle inside her tight with dread. Was now to be the moment her brother stood up and revealed his groundbreaking plan to save the Petty-Squabble empire?

Fibber placed his pad of paper inside his briefcase and clicked it shut. Then, very calmly, he looked up. ‘I am pleased to say, Mother, that I am very close to presenting you with my incredibly detailed and unmistakably profit-soaring business plan that will ensure every spa in the world champions Petty Pampering products.’

Gertrude smirked at her husband. ‘As we always thought, Bernard: Fibber will be the one to save this family.’

Fox swallowed. She felt the need to say something brilliant so that her parents remembered that she, too, was in the room.

And so she coughed. ‘Father, my even more detailed and profity plan for Squabble Sauces is also almost ready. We’re looking at some profit margin… capital… greatness ahead.’ She reached for her tie and put it back on. ‘Asset.’

‘Almost ready isn’t good enough,’ Bernard barked. ‘Not when the head chef of the Neverwrinkle Hotel is refusing to cook with Squabble Sauces ever again because of claims the slimming line we introduced last month gave half his guests food poisoning!’

‘Are the guests okay?’ Fox blurted.

Then she shrank into her blazer. Why had she asked about the well-being of other people? That was not the Petty-Squabble way… Her parents had drummed the family motto into her so many times she genuinely believed that stamping all over other people’s feelings was how you behaved if you wanted to get to the top. Only it seemed she was so dreadfully talentless that she even got stamping on other people wrong.

Gertrude looked on, appalled, and Bernard’s reaction was no better: ‘Hard-headed businessmen and women do not waste time worrying about other people, Fox! Next you’ll be telling us you’re feeling sorry for all those affected by these silly water shortages.’

Fox glanced at the newspaper on the table; the worldwide water crisis still dominated every headline. It hadn’t rained anywhere on earth for months. Rivers and reservoirs had dried up across Europe, crops were failing and plants and animals were dying. Further afield, where droughts were commonplace even before this catastrophe, countries had now been without water for almost a year, so rainforests were withering, famine was a regular occurrence and communities were descending into violence. Meteorologists, scientists and environmentalists had warned about the devastating effects of global warming, but no one had foreseen the speed of this disaster.

Gertrude followed her daughter’s gaze. Then she picked up another grape, squashed it between her fingers and flicked it onto the carpet for someone else to clean up. ‘So long as we have money – which we will have because things always work out in the end for those who stamp all over other people – we will always have access to water. Who cares about everybody else?’

Fox nodded. ‘I don’t plan to lift a finger to help the environment or other people,’ she said firmly.

And she meant it. What she didn’t know was that she was dangerously close to an adventure that would force her to do the exact opposite.

Bernard reached for his clipboard again. ‘I’m going back to the kitchen to throw my weight around some more.’ He looked at his wife. ‘And, since Petty Pampering is on its knees, I suggest you do the same in the spa.’

Gertrude raised a haughty eyebrow at her children. ‘As for you two… It’s high time you started doing your share of the work rather than sponging off us. Petty-Squabble profits are at an all-time low so, when your father and I return, we want to hear your business proposals. No more dilly-dallying with half-baked snippets of information. We want hard, clear, profit-soaring facts.’

‘Disappoint us again,’ Bernard called as he and Gertrude marched towards the door, ‘and you’re both off to Antarctica first thing tomorrow. So, you will stay here until you have those business proposals ready for us!’

The door slammed shut and Fox swallowed.

But, without realising it, Bernard Petty-Squabble had uttered two words which would prove to be his downfall. For telling a child to stay here is about as pointless as telling them to keep quiet. Commands like these are lethal for children because they have next to no control over their legs and mouths.

And though, at this precise moment, Fox was imagining being stamped on by a colony of furious penguins, it wouldn’t take long for the words stay here to echo through her body and stir her legs into disobedience.

She glanced at Fibber. Eating his business plan was no longer an option because he had stashed his papers safely inside his briefcase and only Fibber knew the code to open it. Stealing the briefcase and disposing of it all together, however…

So, without more ado, Fox leapt up, grabbed the briefcase and legged it out of the penthouse suite.

‘FOX!!!!’ Fibber roared. ‘Give me back my briefcase!’

Down the corridor Fox ran, desperately trying to cobble together a plan. Where did you dispose of items for ever and ever and ever? Other than Antarctica…

She glanced over her shoulder to see her brother hurtling down the corridor after her. There was panic in his eyes as well as fury. Fox ran faste

r, charging past the hotel rooms and slipping into the elevator just as it was closing. She heard Fibber bang a fist on the other side of the door, but he was too late. The lift was already sinking down towards the ground floor.

Panting, Fox turned to the lady manning a trolley of cleaning products in the lift beside her. ‘How would you go about getting rid of something very quickly?’

The lady thought about it. ‘My husband once left a pair of dirty socks in a cupboard for twelve years before I found them. They smelt of dead badger.’ She paused. ‘So I burned them.’

Fox gripped the handle of the briefcase. Was real leather even flammable? She looked up at the lady. ‘Got any matches on your trolley?’

The lady laughed, then realised Fox was being serious and that there was a dangerous glint in her chestnut eyes. ‘What exactly is it you’re trying to get rid of?’

Fox considered her answer, then held up the briefcase. ‘My dad has decided he doesn’t want to let work stand in the way of a perfectly good holiday, so he asked me to dispose of this.’

Fox’s heart, despite the wall around it, ached suddenly. Not at the lie – she was used to twisting the truth, though she wasn’t as good at it as her brother – but at the shape of her world, which was unnatural and unfair and unbelievably cruel. And, to her horror, she felt tears rising up inside her. She pursed her lips at the lady and thought of something foul to say.

‘If you don’t come up with a sensible plan for the disposal of this briefcase immediately, I am going to lodge a complaint to ensure the disposal of you from the Neverwrinkle Hotel by dinner time.’

The lady blinked and then sighed as if she was used to dealing with guests like this. ‘If the briefcase is worth something, and by the look of those buckles I’d say it might be, then I wouldn’t get rid of it. I’d take it to the antiques shop in the village. They take all sorts of fancy objects to sell on to customers across the world and they’ll give you a good price.’

Although Fox had always been taught to think of ways to make money, she didn’t imagine there’d be much need for lots of cash in Antarctica, but then a rather marvellous idea occurred to her. Perhaps she could use the money to bribe the postal service to send her somewhere else. Somewhere with fewer penguins and more people.

The lift shuddered to a halt and the door opened.

‘You turn right out of the hotel,’ the lady called after Fox, who was already sprinting away. ‘Then down the street, past the train station and, when the road bends left, take the first little side road. The shop is tucked in there.’

Fox didn’t turn to say thank you – partly because it didn’t occur to her and partly because she could see Fibber leaping down the last of the fire-escape stairs and tearing across the foyer after her like some small, deranged business tycoon.

She flung herself into the cobbled street, squinting through the afternoon sun at the rows of higgledy-piggledy coloured houses with peaked terracotta roofs climbing into the bright blue sky. Last summer, tourists had flocked to the village of Mizzlegurg, drifting around on bicycles and eating ice creams under the restaurant awnings, but since the water crisis Mizzlegurg, along with so many holiday destinations across the globe, had become a quieter, less visited sort of place.

The signs of the water shortages were subtle, but they were there nonetheless: the flower boxes beneath windows were empty because there was a ban on watering plants that were purely for decorative purposes; numerous restaurants had closed because the increase in food prices due to failing crops meant fewer people could afford to eat out; the hotels were half empty because they could only supply a limited amount of water to guests; and the reservoir just outside the village that generated water for the locals was running dangerously low so each building had a water ration.

Fox ignored all of this and carried on running, knowing that Fibber was hot on her heels and that somehow she’d have to shake him off when the road split. The train station burst into view, just as the cleaning lady had said it would. Only it didn’t have multiple platforms and trains all under the same roof, like others Fox had seen. In fact, Mizzlegurg Station had no roof at all. It was simply a train track flanked by two platforms and a little wooden hut, which might have been a ticket office – though it was as empty as the platforms. Behind the station, Fox could see mountains covered in trees that had once been tall and green and bursting with leaves, but which were now bent and brown and shrivelled from lack of water.

She sprinted past the station, eyes peeled for the side street she hoped to vanish down without her brother seeing. And so intent was she on finding it that she didn’t give Mizzlegurg Station another thought. But if Fox had been moving a little more slowly, and if she had been paying a little more attention, she might have felt the faint but unmistakable tingle of magic stirring.

Because, in precisely forty-seven minutes, an event was going to occur at Mizzlegurg Station that would change the lives of the Petty-Squabble twins for ever.

When the road bent left, Fox bolted down the side street, then practically threw herself into the antiques shop. It was quiet inside and specks of dust hung in the air, suspended in the sunlight above the clutter of antiques like thousands of indoor stars.

Fox glanced around. The shop was full to bursting. Where tables laden with old-fashioned weighing scales, copper jugs and dusty cutlery ended, pianos, grandfather clocks, old trunks and wardrobes began. There were spinning globes perched on threadbare armchairs, ship wheels wedged into corners, jewellery boxes stacked one on top of the other and chandeliers hanging from the ceiling. Every nook and cranny was filled with junk. Fox blinked at it all in disgust.

Then she stiffened as she heard Fibber’s footsteps thundering closer. Would her brother shoot on down the road into another shop or had he sensed, as twins often manage to do, that Fox had turned in here? She shoved his briefcase under a piano to buy herself a little more time, then seconds later Fibber crashed into the shop, sending a pile of antiquarian books flying.

He turned on his sister. ‘Where is it?’

Fox could hear the panic in Fibber’s voice, but she noticed he’d hung back on unleashing the usual insults: squit-face, moth-brain, scum-breath. Fox wasn’t exactly a fan of these terms, but at least when Fibber used them she knew precisely where she stood. She had no idea what game he was currently playing with his recent silences and his lack of stamping all over other people. She plucked a rusty telescope from a shelf and turned it over in her hands.

‘I dumped your briefcase in a bin on the high street.’ She paused. ‘So, if I were you, I’d go and find it before it’s carted off for ever.’

Fibber snatched the telescope from Fox and hurled it over his shoulder. ‘I didn’t see you hovering round any bins.’ He straightened his tie to show that he meant business. ‘What did you do with it?’

‘If you keep pestering me,’ Fox muttered, ‘I’ll dump you in a bin.’

There was a cough from the back of the shop and the twins whirled round to see an old man emerging from behind a wardrobe. He had dark, wrinkled skin and a fuzz of grey hair and in his hand he held a duster.

‘I was once plunged head first into a bin,’ he said, ‘by a boy called Leopold Splattercash.’ He shuddered. ‘Dreadful human being. Used to chew his own toenails.’ The man tucked the duster into his apron. ‘So, what can I do for you two then? Bearing in mind that I don’t, regrettably, stock any bins in this shop.’

‘You should do,’ Fox mumbled. ‘You’ve got enough rubbish in here to fill hundreds.’

The old man picked his way through the antiques towards the twins.

‘Don’t even try to sell us any of this junk,’ Fox said haughtily. Then she kicked the old-fashioned writing desk beside the old man, which sent the inkpot that had been resting on top clattering to the floor, and added: ‘Petty-Squabbles never buy second-hand; we don’t need to when we can afford the best of the best.’

She glanced at her brother, expecting him to say something equally rud

e, but he was too busy rooting through the antiques for his briefcase.

The old man picked up the inkpot, set it back on the writing desk and blinked at the twins. He didn’t often come across children. His customers tended to be adults and he and his wife had never had a family. But he had remained optimistic about them nonetheless, because he knew, from personal experience, that when worlds and kingdoms needed saving it was children who stepped in to sort things out. But the two in front of him now didn’t seem the world-saving types. At all.

And so it was with a great deal of surprise that the old man noticed the blue glow coming from the half-open drawer of the writing desk the girl had just kicked. He bustled towards it and drew out a small velvet bag.

‘Impossible,’ he murmured, tipping a marble into his palm.

The sun had dipped behind the street now and in the gloom of the cluttered antiques shop the marble was sparkling with a fierce little light all of its own.

Fox plucked idly at her plait. ‘I suppose you’re going to try and claim that this marble is one of a kind and worth stupid amounts of money.’

Even Fibber, who was still worried about finding his briefcase, couldn’t help but look up at the glowing marble. ‘What’s it got inside it? Batteries? Miniature lights?’

‘Magic,’ the old man whispered.

Fibber plucked the marble from his wrinkled hand, turned it over in his palm, then rolled his eyes. He was too old to believe in magic. But, just as he was about to hand the marble back, the man reached out and grabbed Fibber’s wrist.

‘The world is not as you know it. But if I was to tell you the truth – that we only survive because of four unseen, unmapped, magical kingdoms that conjure weather for our world – you would laugh at me, just as I laughed years ago when I was told the same thing.’

Fibber tugged his arm free, but the old man kept talking, his voice low and urgent as if, perhaps, he had been waiting for this conversation for a very long time.

‘You’ll have learnt, of course, about the terrible hurricanes seventy years ago, which almost tore our world apart. Scientists have never understood why those hurricanes stopped as quickly as they started, but that’s because it had nothing to do with science… It was because of magic.’

Everdark

Everdark Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll

Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll Rumblestar

Rumblestar Jungledrop

Jungledrop The Night Spinner

The Night Spinner Soul Splinter

Soul Splinter Winter Magic

Winter Magic The Dreamsnatcher

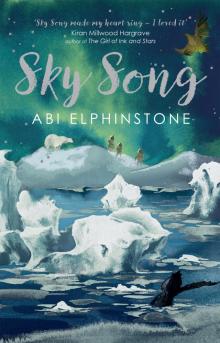

The Dreamsnatcher Sky Song

Sky Song