- Home

- Abi Elphinstone

Winter Magic Page 12

Winter Magic Read online

Page 12

The room he found himself in was a church. As his eyes became more accustomed to the gloom, Fergal could make out the altar at one end, the font at the other, the brasses set into the floor.

‘You have to come. You have to help me.’ He said it so many times – like the chorus between the verses of a song. ‘There’s Mum and Dad and Ella and Zizzi . . . You have to come. You have to help me. Dad blew the horn three times, and next thing you know . . . You have to come. You have to help me. If I had a shovel . . . the air . . . they won’t be able to breathe! You have to come. You have to help me!’

There was no dash to fetch spades, no stampede for the door. Perhaps the church, too, had just been buried by the avalanche . . . though they did not have the look of people newly hit by disaster.

‘Fetch the Teller,’ said one of the elderly men, his back as bent as a question mark demanding of an answer. ‘She can tell the balach how we sinned and were punished for it.’

‘No! I don’t want to know . . .’ Fergal began, but they were either deaf or refusing to hear his pleas for help.

They brought in – literally carried in, by armpits and elbows – a prodigiously old, blind woman, and sat her on a sack of ancient wool. She seemed to be gearing up to tell a story. Fergal had no time for stories! Could they not see that precious moments were going to waste? He writhed at the slowness of their speech and movements. When the woman spoke, she laid down each word like a playing card in an unbelievably slow game of Patience.

‘’Twas Christ-mass. A Sunday Christ-mass, a thousand year past.’ The eyes of the villagers glazed over. Their lips moved silently, speaking each familiar word in time with the Storyteller. They had heard it a thousand times. ‘We were exceeding happy. Fowl were cooking. Our childer were clad in new clothes. New clothes at Christ-mass, new clothes at Easter: that was the old way. Old Popser was mulling ale for after the Mass. We had brought along our beasts for a blessing. There was a piper among us – and a wee drummer-boy, too: we had learned a new carol to sing. Our hearts were merry. The cold was rare. The stove sang with the heat in its belly. In our mouths was music. In our souls was jollity. We gave no thought to our badness. We gave no thought to our wickedness. The music of the pipes was so braw that one Mary of the Grange did begin to dance – here in the very midst o’ the kirk.’ And the blind Storyteller pointed at the pulpit. A dozen hands made the same gesture, pointing (more accurately) at the aisle. Fergal wanted to shake her – to yell that nothing – nothing – that had happened in their mildewed past mattered as much as the people suffocating in that car buried under the snow outside . . . But it was as if he had been caught in a spider’s web of words and even his mouth was sutured shut with gossamer.

‘Others were roused to dance also. Then did the piper play more loud. Men and women laid hold on the bell ropes and pulled mightily till the bells swangeth to and fro and the skies were knocked with clamouring!’

A change came over the Storyteller at this point, and all the faces fell into a similar expression of sorrow.

‘Then awoke the angels and spoke one to another. “Who wakes us with this unholy noise? Is it no’ Sunday? Is it no’ the day o’ the Lord? Is it no’ a day of silence? Who are these noddies and why do they not think upon their sins and wickedness, and kneel down and beg forgiveness?” ’

‘Because it was Christmas?’ suggested Fergal.

The interruption was greeted with fifty shocked expressions. No one had ever interrupted the Storyteller while she retold the Legend of Fuachd Munro. She reeled in her seat. Someone tucked a blanket around her, pulling it up over her head so that only her huge, hooked nose was still visible.

‘Then did the angels weep tears of red blood. “Let judgement fall on every head!” said the angels. “Let the mountain open and let Winter swallow them up. Yeah, and their childer after them, even unto the Final Day!” Then came down Judgement upon the souls of Fuachd Munro. Then came down snow and tree, rock and tears of blood. And we were sunk into darkness and the place of wailing and chattering of teeth.’

The Storyteller gave a phlegmy cough and glared in the vague direction of Fergal. She also gave a yelp of alarm as something licked the hand she had left dangling outside the blanket. Summer had got over her shock and was on the prowl for titbits. Obviously, the Storyteller had been fetched away from her lunch to recite, and still had traces of food on her fingers.

As the coughing subsided, she took up her story again. Even Summer sat down to listen as the words fell from that age-puckered mouth, like dizzying snow. She spoke of a Christmas 800 – maybe 900 – years before, when snow had been falling past the thick, wrinkled window-glass of the kirk. All those years ago, the assembled villagers of Fuachd Munro had been trapped inside the church when, like the roar of a hundred canons, a torrent of rock and snow had fallen on the kirk. Inside his head, time stopped for Fergal, too, and he could vividly picture them desperately boarding up the windows with bench seats, to keep out the weight of frozen earth pressing against the glass.

‘That was the Christ-mass Day of Judgement,’ said the Storyteller. ‘Though we are suffered to live on, generation by generation – being born, marrying, dying – still, for us, Time stopped that fearful day when we transgressed.’

The assembled crowd uttered a sorrowful sigh as the recital ended.

Fergal, though, was once again unable to breathe – buried under a freezing drift of words. His hand clawed at the air over his head. He must get out. He must get help. There was surely some door out of this subterranean tomb of a place! He ran to and fro in search of one.

Over the centuries, the villagers had made their prison bigger, digging tunnels into the mountain, replacing their houses-above-ground with underground warrens, like rabbits. Except that rabbits go outside. Rabbits graze grass, dig up carrots, catch the sound of the wind in their long ears, and flash their fluffy scuts in the bright sunlight. Fergal realized, with growing horror, that the people of Fuachd Munro never saw sunlight. They did not try to escape. They had remained for ever where they thought they deserved to be: sealed into the past by a roof of slate, earth, ice and snow.

‘Rubbish!’ he spluttered, finally recovering the power of speech . . .

Fifty throats drew in the damp and chilly air in sharp gasps.

‘Well, it was an avalanche, wasn’t it? Like the one just now. You have to come. You have to help me. Give me a spade at least! But someone do something! You can’t just sit there! We have to be quick! There’s no time!’

But nothing could hurry the people of Fuachd Munro. He saw it in their shineless, doubting eyes. No time? There was plenty of time. Time was the iron prison ball that had been chained to their ankles hundreds of years before. Time was the sentence that had been passed on them by the angels, and they must spend it underground, meekly, not rushing about at the bidding of this rowdy boy.

‘Will I show you the angel tears?’ offered the girl who had lowered the chandelier.

Her name was Mariah, and she alone seemed excited about Fergal dropping in. She dabbed him dry of snow with a scratchy piece of sacking. The others were unsettled by his sudden arrival, annoyed about the hole in the church roof, and positively scared by his noisy disrespect for the Storyteller. They told Mariah to keep away from him.

But Mariah led Fergal to the altar and, because she was about his age, and because her hand was warm on his, he let himself be led. There, in a box carved from the root of a yew tree, lay a dozen shrivelled little balls the colour of beetroot. Mariah’s colourless eyes shone with wonder at the sight of them rolling around in the box.

‘They’re holly berries,’ said Fergal. ‘They’re dried-up holly berries.’

Already as pale as milk, Mariah’s skin turned paler still. ‘Angel tears.’

‘Nope. Anyway, why does it matter? Mum and Dad matter. Ella and Zizzi matter. I just want a spade and a way out.’

‘There is none.’

‘There must be. You must go out to get food.’

‘Mushrooms. Potatoes. Rabbits stray in upon us. Mice. Worm potage is wholesome fare.’

‘I’ll pass,’ said Fergal. He had a feeling she was lying to him and not just about the worms. ‘You must go out to get those candles. The makings. Bees? Something.’

‘Tallow.’ Which stopped the conversation, because neither of them knew what tallow was made of.

‘You couldn’t live like this. People can’t live like this,’ he insisted, at which Mariah shrugged and led him on a tour through a warren of tunnels where pale roots reached out of the soil to catch in his hair. Side chambers led off to animal pens with sheep in them – descendants of those beasts brought into the church for a Christmas blessing, Mariah told him. There were warming places with grates burning charcoal; and sleeping holes, and ‘dripping places’ where leaks of rain and snow melt were captured in bowls, for drinking. Like angel tears.

They must have spades, he thought, to have dug these. He looked for daylight – an escape route – but found none. ‘I’ll just have to go out the way I came in. You’ll have to haul me up to the roof again. You have to.’

‘I cannot. I dunna have the strength.’

Fergal looked at his watch: it had stopped when the snow fell on him. He pocketed charcoal from one of the grates, and when they got back to the church, he began to draw on the wall. The villagers of Fuachd Munro stared at him in outraged horror, but no one quite dared to wrestle the charcoal out of his hands. What did he care what they thought of him? They were old people – even the younger ones behaved like the old – slow-moving, out-of-date, timid and too stupid to see what was staring them in the face.

‘This is a mountain,’ said Fergal, and drew one. ‘The snow falls on it – fall-fall-fall.’ He dotted the granite wall with black snowflakes. ‘It freezes to the mountain when it’s winter and very cold – freeze-freeze-freeze. Then the sun shines on the mountain – sun-sun-sun. See?’ He drew a sun – something the people of Fuachd Munro had never seen, but did believe in because there were carvings in the church of suns and moons decorating the beams. ‘One day, there’s much too much snow hanging about. The sun shines on it and, under the snow, the ice melts a bit. Not so sticky, you know?’

‘Sticky,’ repeated a voice here, a voice there. Sticky. It was not a word they knew. They pictured walking sticks and tree roots.

‘Then if there’s a big BANG or shout or something, it makes the air shake, and the snow shakes, and the ice can’t hold on to the rock, and whoosh it all comes rushing down the mountain!’

As he said it, Fergal relived it, the sharp blasts of the car horn, the aching groan and the rumbling rush, the tumbling noise and confusion, and the cold and terrifying career of snow and trees and bushes down the mountainside engulfing everything in its path. He drew a car and, in it, four heads . . . before his knees gave way and he sank into a crouch of fear and horror.

‘Dad sounded the horn, and it made an avalanche come down. I have to get them out. You have to come. You have to help me.’

‘So . . . not the angels’ doing?’ said Mariah, and somebody punched her in the back.

‘Science!’ pleaded Fergal. ‘We did it in Science at school! You know? Avalanches?’

But the very word was foreign to them. ‘Avalanche.’ It had no meaning. It was not Scottish, not centuries old. It was not a word that had ever fallen from the lips of the Storyteller. They must know, of course, how the mountain sometimes shivered, groaned and terrified them with its rumblings. Surely the upheaval overhead must have broken the tiles on the roof before and sprinkled them with snow. But clearly it had never brought them a boy before – or a lesson on avalanches.

‘Dunna heed the beast. S’a demon,’ said a man dressed all in black. He seemed to wield some kind of authority for the others cleared a path for him as he advanced on Fergal. ‘’Tis sent by the Devil to fill our minds with untruths. Mark me, ’twill tell us soon that dancing is lawful, also the making of music and the clapping of hands and the ringing of bells in merriment.’

‘Course it is! It’s just a bit noisy, that’s all! It made that avalanche happen that fell on you.’

That word again. That mystical, meaningless word: avalanche.

Fergal appealed to Mariah. She seemed like a sensible girl. ‘Nothing wrong with dancing, is there?’

Mariah took several steps backwards.

Now Fergal was not one for dancing. It was embarrassing. He never knew what to do with his arms and legs, and sometimes girls took it for an excuse to hold hands. His sisters danced a lot: it was embarrassing . . . but not actually wicked. And he had to prove that. So, breaking the habit of a lifetime, Fergal pulled himself upright again and began to dance, lumbering about like a drunken bear. The only song he could call to mind was not the least bit churchy and, in his fright, he could not even remember the words.

To his huge relief – and aching embarrassment – Mariah took hold of one of his hands and joined in. He could see in her eyes the terrified surprise at her own daring. They danced idiotically, like frogs in a tumble-dryer, singing:

‘It’s time to dum-di-dum-dum,

It’s time to light the lights!

It’s time to get things started,

Dah-di-da-di-da tonight.’

Summer barked excitedly, unnerved. Her noise was huge in the big, hollow space of the church. What if the barking brought down a fresh avalanche?

But that was not what stopped the people dancing. They stopped because the man in black snatched the walking stick from the aged man and came at them. The stick’s owner toppled over, and somehow that was Fergal’s fault, too. A universal purple rage rose up like floodwater gushing into the church. It fetched everyone to their feet. It made them gasp and hop about. It made them raise their fists over their heads and wade towards the two young people cavorting in the gloom. They fell over the dog. They collided with each other. But they also congealed into a mob, with one thought and one thought only: Fergal was a disaster that must be averted before Heaven’s rage came down on them again, as it had done centuries before.

‘S’a demon sent to tempt us with the forbidden things!’ wailed the man in black, slashing the air with the walking stick.

Fergal grabbed Mariah’s hand again and fled. He fled towards the font and the church door which had not opened for 800 years: a door with fathoms of earth and snow behind it. He fled into a granite cul-de-sac with no way out. When Mariah made for a ladder rising towards the wooden loft, he followed her up it: there was nowhere else to go.

‘I’m sorry,’ gasped Fergal, but only to Mariah, not to the rabble pursuing him. It was rage against them, and the thought of his sisters and mother and father, that lent his bruised and shaking legs the strength to reach the ladder’s top.

Once, sunlight had squeezed between the plank walls of the bell tower: now it was buried under hard-packed earth and all the two could make out in the darkness were two loopy bell ropes hanging down like dusty plaits. Their pursuers were already starting up the wooden ladder, shouting and shaking their fists. Though there was nowhere higher to climb to but the cobwebby ceiling, Mariah flung herself at one of the ropes, Fergal followed her example, and they climbed, jabbering with fright, like chimpanzees shinning up jungle greenery. The man in black struck at their legs and then at the wall beneath their disappeared legs, little pieces of wood breaking off the walking stick and flying about.

Now it just so happened that, high above them, the ancient bells had recently been laid bare by the latest avalanche. Earth, rocks, the pine cones and needles of generations of pine trees had been swept aside by the latest collapse of compacted snow. The bells had been left bulging out of the ground like giant, dirty helmets. Tugged on by the efforts of boy and girl to climb, the bells writhed now within the ruins of their rotten wooden bell turret, which fell to pieces around them. They writhed and they rolled – first with a dull clank and then, as they shook off soil, with a clanging splendour. The ropes were tugged out through the loft roof with such

force that the lashing rope-tails tore a great hole through wood, earth and snow. Then the bells tumbled down the slopes of Fuachd Munro, noisy as twin fire engines racing to a fire in the valley.

It was a noise loud enough to shiver the snowcap off Everest. It was a noise alarming enough to make angels wake and jump overboard from their clouds in terror.

Everyone in the subterranean church held perfectly still as, second after second, the bells spilled their rusty ringing down the mountainside. Nobody breathed. Nobody moved. The man in black stood with the stump of the walking stick raised over his head. Fifty heads cocked sideways to listen for Judgement to awake and hurl its thunderbolts.

But the avalanche which had buried the car had rid Fuachd Munro of all the snow curtains, dead trees and loose earth that had built up over winter. No thunderous rumbling came; only a profound silence after the bouncing bells had come to rest in the River Fuachd.

‘Sorry,’ said Fergal. ‘I didn’t mean to break things. But I have to get out. And you have to come, too. All of you. You have to help me get them out. They’ll die if you don’t help. And that would be wicked.’

Like statues they still stood immobile, heads cocked, listening for punishment to fall on them from Heaven. Then their eyes flickered in the direction of the boy who had laid hands on the forbidden bells and broken every rule.

‘Who?’ said Mariah suddenly. ‘Who is it in the coach?’

He looked across at her. It was more than just a question: he could read it in her face. But his thoughts were wading in treacle. Despair was getting the better of him. Already it was too late. It must be far too late. ‘Mum. Dad. Zizzi . . .’ Even as he answered, he knew they would not understand: ‘Mum’, ‘Dad’: those were twenty-first century words. Not known at all to ye olde, olde world. What he should have said . . .

Everdark

Everdark Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll

Zeb Bolt and the Ember Scroll Rumblestar

Rumblestar Jungledrop

Jungledrop The Night Spinner

The Night Spinner Soul Splinter

Soul Splinter Winter Magic

Winter Magic The Dreamsnatcher

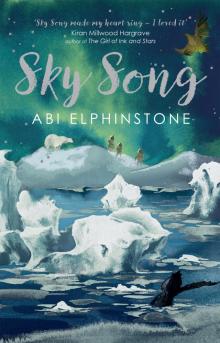

The Dreamsnatcher Sky Song

Sky Song